Original Reviews: London (1986); Broadway (1988)

5 posters

Page 1 of 1

Original Reviews: London (1986); Broadway (1988)

Original Reviews: London (1986); Broadway (1988)

I'm making this thread a sticky so that anyone who comes across another review that I haven't posted that is either a review of the London production from 1986 or the Broadway production from 1988 can add to this. Would be good to have the complete set!

I'll start off by posting the London reviews that I have in electronic form, then I'll make a post containing the Broadway reviews I have.

I'll start off by posting the London reviews that I have in electronic form, then I'll make a post containing the Broadway reviews I have.

LONDON REVIEWS 1986

LONDON REVIEWS 1986

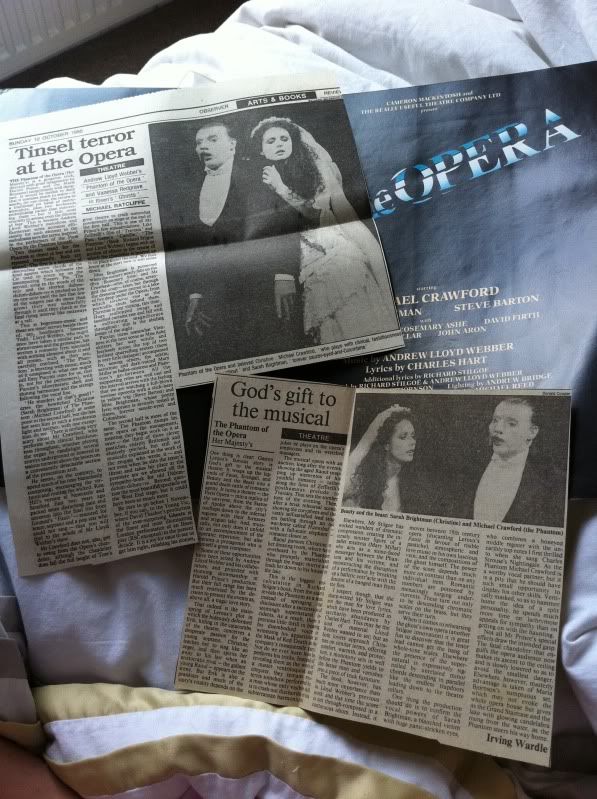

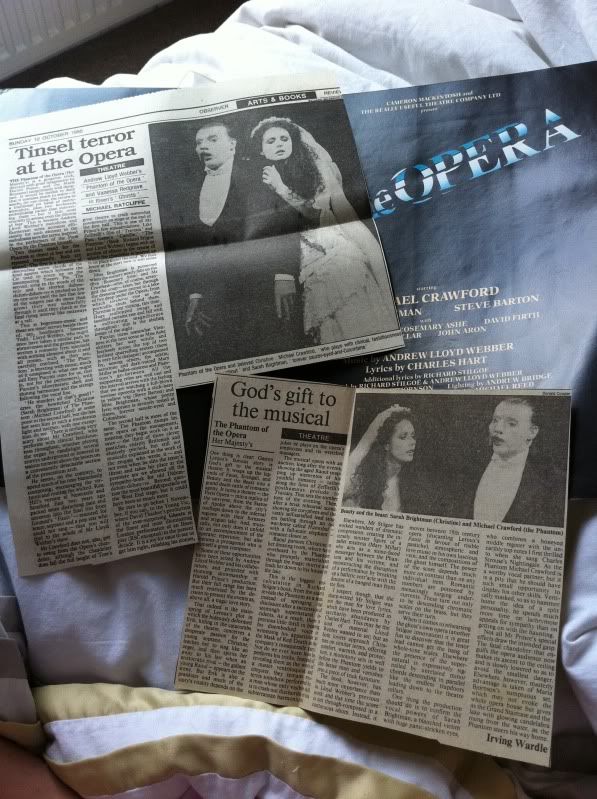

From The Times (Friday October 10 1986), The Arts section

God's gift to musical theatre

by Irving Wardle

The Phantom of the Opera

Her Majesty's

One thing is clear: Gaston Leroux's famous story is God's gift to musical theatre. It wraps up the legends of Faust, Svengali, and Beauty and the Beast into a grand final death rattle of the romantic agony. It turns a theatre -- the Paris Opera -- into a replica of the universe, from the Statue of Apollo above the city's rooftops down to the infernal regions with their furnaces and stygian lake. And, musically, not only does it unfold to an accompaniment of the operatic repertoire, but also features a protagonist who is himself a great composer.

Some of these opportunities have been seized by Andrew Lloyd Webber and his collaborators, and projected with stunning showmanship in Harold Prince's production. But their full range has been much restricted by the decision to present the events above all as a tragic love story.

That indeed is the mainspring of Leroux's plot in which the hideously deformed Erik, hiding in the catacombs of the theatre, conceives a desperate passion for the young soprano, Christine, teaches her to sing like an angel, and then spirits her away to his lair when an aristocratic rival -- the gallant young Raoul -- appears on the scene. But Erik is also a prankster in the ETA-Hoffmann traditional and much of the story's vitality depends on the jokes he plays on the opera's employees and its wretched managers.

The musical opens with an auction, long after the events, showing the aged Raoul snapping up mementos of his youthful romance -- rather along the lines of Zeffirelli's posthumous prelude to Traviata. That sets the sombre tone of the evening. And after a brisk rehearsal scene, showing the coryphees and the vastly self-satisfied lead singers battling through an old war-horse called Hannibal, with a full-scale elephant, romance closes in. Raoul pursues Christine to her dressing room where he is overheard by the Phantom, who promptly materializes through the magic mirror and leads her down to his house by the lake.

This is the biggest miscalculation in Richard Stilgoe's book: as it reveals the Phantom as a man from the start instead of springing that disclosure after a succession of seemingly supernatural incidents. As a result, there is precious little thrill in hearing his disembodied voice or witnessing his apparition as the Mask of Red Death at the company's masquerade party. Nor do we ever learn how he performs his tricks. Instead of revealing them as the work of a master ventriloquist and conjurer, they remain unexplained mysteries somehow performed by a man whose only visible skill is to crash out dischords on his subterranean harmoninium.

Elsewhere, Mr Stilgoe has worked wonders of dramatic compression: creating the intensely sinister figure of a ballet mistress (Mary Millar) who acts as a stone-faced messenger between the Phantom and his victims; and reconstructing the disruption of a performance by breaking up a balletic entra'racte with the descent of a hanged man from the flies. I suspect, though, that the sharp-witted Mr Stilgoe was not the man for the love lyrics; which have been produced in saccharin abundance by Charles Hart. This may be the kind of material Lloyd Webber wanted to set; but as both lovers approach Christine on similar terms, offering comfort, warmth, and protection, a monotony sets in well before the Phantom yields to the better man and vanishes into a trick piece of furniture.

The book, however, has much more importance than in his previous work; and this time the score is not through-composed in a continuous idiom. Instead it moves between 19th century opera (discarding Leroux's Faust in favour of risible pastiche), atmospheric and love music in his own lucious vein, and the compositions of the ghost himself. The power of the score depends much more on contrast than on any individual item. Lullaby like romantic numbers are poisoned by menacingly surging undercurrents. These turn out only to be descending chromatic scales on the brass, but they serve their turn. When it comes to rehearsing the ghost's own opera (another Stilgoe innovation) it is great fun to discover that tenor lead cannot get the hang of whole-tone scales. Elsewhere the presence of the supernatural is expressively signalled by unrelated minor chords descending in parallel like the endless trapdoors leading down to the cellars of the theatre.

One thing the production should do is to confirm the vocal powers of Sarah Brightman, a blanched victim with huge panic-striken eyes, who combines a honeyed middle register with the unearthly top notes I first thrilled to when she sang Charles Strouse's Nightingale. Michael Crawford as the Phantom is a worthy vocal partner, but it is a pity that he should have such small opportunity to display his other skills.

___________

It’s fantastic, fabulous and phantasmagorical!

John Blake, Daily Mirror, 10th October 1986

It's fantastic, fabulous and phantasmagorical! From the eerily flickering lights that greet you outside Her Majesty's Theatre to the last, glorious curtain call, Andrew Lloyd Webber's long-awaited new musical, Phantom of the Opera, is a triumph.

The special effects are among the most spectacular ever seen in the West End.

The music is every bit as memorable as one would expect from the man who wrote Evita, Starlight Express and the rest. But most of all, the show belongs to Sarah Brightman and Michael Crawford, who soar and swoop through their hugely demanding roles like eagles.

After all the well-publicised false starts and back-biting, Lloyd Webber has created a musical which deserves to be around well into the next decade.

The story is based closely on the original novel of 1911 - unlike most of the Phantom of the Opera films which have been made over the years.

Michael Carwford's Phantom hides his hideously disfigured face by skulking in the stage caverns and pools deep beneath the Paris opera.

His passion for music is the only thing which gives his life meaning until he becomes obsessed by Sarah Brightman's Christine - a young opera singer whose beauty is matched only by the purity of her voice. He coaches her in secret while visiting dreadful catastrophes on anyone who refuses to advance her career.

A hanged scene shifter is suddenly hideously dropped on to the stage in the middle of a performance. A vast crystal chandelier crashes on to the audience.

As the phantom becomes more fiendish so Christine becomes increasingly mixed in her feelings towards him.

A dreadful climax is fast approaching.

The eerie sets of the unfolding drama - great stages filled with mist and shining candles - are interspersed with all the colour and spectacle of the operas being prepared and presented at the theatre.

Despite all the "ghost train" theatricals the greatest thrills of the show come from Michael Crawford.

He not only sings superbly but also captures the torment of the Phantom perfectly.

If you only see one show this year, make sure it is this one!

_____________

Jack Tinker, Daily Mail, 10th October 1986

Four words sum up the unstoppable success of Andrew Lloyd Webber's triumphant re-working of this vintage spine-tingling melodrama. Stars, spectacle, score and story.

Together they add up to that old magic ingredient: theatricality. There is simply nothing on earth to transport you so quickly or so far into phantasy than a feast of illusions. And Hal Prince's production stints nothing in providing an unending banquet of the stuff.

When I get my breath back from gulping down as much as is decent in one sitting, let me deal with each item in turn.

First the star and the evening's greatest surprise. Were it not that I personally know Michael Crawford's singing teacher to be the kindest and mildest of men, I would swear that Mr Crawford had sold his soul to the Devil to acquire the rich and powerful voice with which he floods the theatre and holds us hypnotised in his presence.

The mask that for most of the evening obliterates half his face only hints at the physical horrors beneath it. But, by the time his golden-voiced protégé has torn it aside to reveal a peeling skull and rotting flesh, he has utterly established the phantom as one of the enduring tragic figures of the modern musical; a man with a tender, gifted and loving soul whose only crime was to have been born a freak.

It is surely one of the great performances, not only in a musical but on any stage and in any year.

In this Mr Crawford is indeed fortunate to be partnered by someone as illustrious and exotically voiced as Sarah Brightman. I can think of no other actress whose glorious operatice range can match a stage present so delicately vulnerable or exquisitely beautiful.

On now to the full throttle spectacle that Maria Bjornson has conjured up to encompass all the diverse elements of the evening.

Giant chandeliers plummet from on high; great gilded angels bear Mr Crawford skyward as he sings out his heart to heaven; a lavish fancy dress masquerade underlines the sinister nature of disguise; high-camp pastiches of less than grand opera strike just the right note of comic relief while a lake of lights floats us down to the Phantom's lair beneath the great Opera House of Paris.

As for the score, it soars and instils itself into the mind like some half-forgotten refrain from Verdi, taking the story line on in great sweeps of musical sound. In its unabashed romanticism it reminds us that the Phantom is at heart a simple take of unrequited love, as inspiring and moving it its way as Romeo and Juliet, or more appropriately Beauty and the Beast.

Yet to underline the sheer theatricality of the piece the Phantom does nothing so mundane as to die for love. He vanishes in a blink before our eyes.

True there are faults but to pick them here and now would be churlish and irrelevant. Mr Lloyd Webber has another long-term tenancy and his wife has established herself as a star of status.

As for Michael Crawford there is just no other artist in the country today who can touch his command of a stage or match his daring in meeting a new challenge.

______

Richard Barkley, Sunday Express, 12th October 1986

Andrew Lloyd Webber's new musical The Phantom of The Opera is a gorgeous operatic extravaganza that is a thrill to the blood and a sensual feast for the eye.

High melodrama is the key note from the start when the rich splendours of a rehearsal at the Paris Opera of Hannibal, complete with slave girls and elephant, is brought shiveringly short by the ghostly intervention of the phantom.

As warning blasts of brass from the 27-piece orchestra trigger our apprehension, the half-masked phantom appears behind chorus girl Christine's mirror to lure her down through a labyrinth to the candle-lit intimacy of his subterranean world.

Using subtle vocal intonation and body movement in an extraordinarily moving performance, an almost unrecognisable Michael Crawford devastates us with the anguish and despair of the phantom, a freak ultimately failing in his struggle to overcome the disfiguring mistake of nature that has rendered him unloved since birth.

Sarah Brightman's wide-eyed beauty and soaring soprano voice make something individual and touching out of Christine's tussle between pity for the phantom and love for her friend and admirer, the Vicomte de Chagny (Steve Barton).

It is a lyrical high point when she expresses her sympathy for the phantom in Wishing You Were Somehow Here Again, a melody that carries an eerie echo of the Pie Jesu from Lloyd Webber's Requiem.

Meanwhile the evening, rooted in the Gaston Leroux novel, dispenses a great rolling buffet of musical delights.

And there is one particularly striking set piece stage by Gillian Lynne under Harold Prince's direction as the huge drapes fall back to reveal the company poised on the Opera's grad staircase for a masked ball, which is performed to the seductive syncopation of a bolero-like rhythm.

But as you rock back in your seat from sudden sunbursts of light, the reek of gunpowder and the impact of a chandelier crashing from the roof above the stalls to the stage, Michael Crawford's magnificent performance permeates all to produce a dramatic unity ultimately aching with pathos.

_________

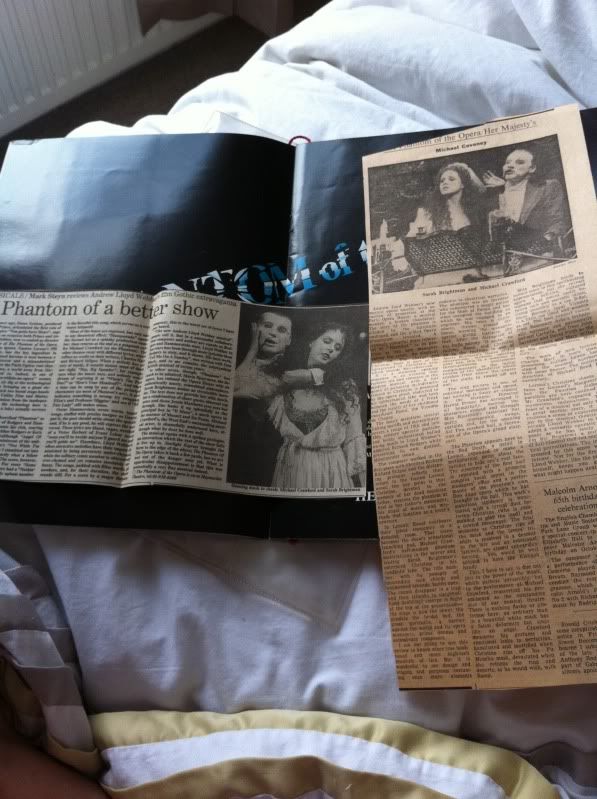

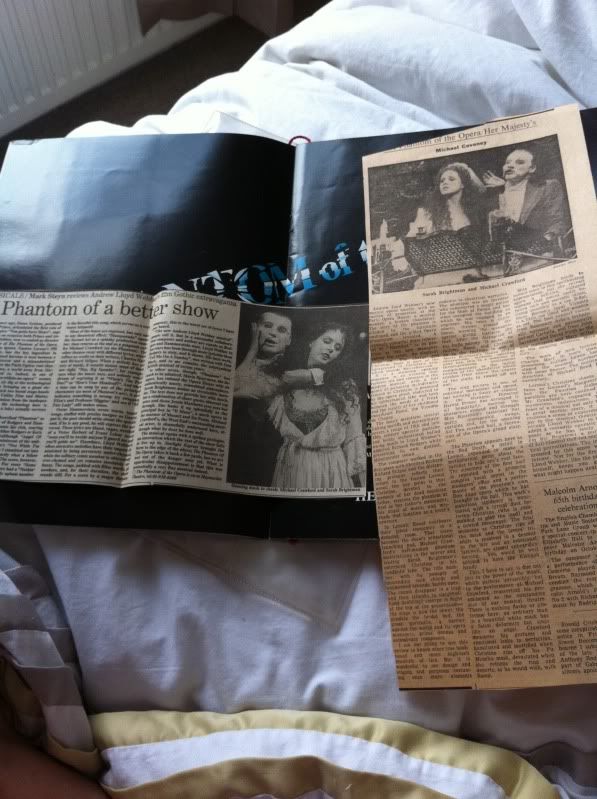

Mark Steyn writing for The Independent, October 11 1986

Thirty years ago, Damn Yankees , produced by Harold Prince, articulated the first rule of musical theatre: “You gotta have Heart”, sage advice which both Prince and Andrew Lloyd Webber, now re-united as director and composer of The Phantom of the Opera, have on occasion chosen to ignore. Gaston Leroux’s 1911 novel, however, has the key ingredient in spades. A confused heroine is torn between a handsome aristocrat and a misunderstood misfit who haunts the Paris Opéra - real emotion, a world away from Starlight Express and co. Indeed, in one of Phantom ’s “opera-within-an-opera” scenes, Prince manages a sly dig at the technological gimmick shows by bringing on a giant elephant, inside of which two bored stage-hands are playing cards. Unlike Time and Mutiny, where it diverts attention from the inadequacies of the drama, the technology here (a crashing chandelier, a lake) actually services the show.

Lloyd Webber has described Phantom as a return to the values of Rodgers and Hammerstein, and at moments his rich, soaring melodies are worthy of either Rodgers or Kern at their most lyrical (although “Angel Of Music” struck me as reminiscent of the middle section in Sondheim’s “Not While I’m Around” and, blow me, as I stumbled out into the Haymarket, that’s exactly what a fellow first-nighter was singing). The score, however, Is dreadfully unbalanced. For every “Some Enchanted Evening”, Rodgers had a "Nothin' Like A Dame”. Here, the only upbeat number is the forceful title song, which serves as a very heavy leitmotif.

Most of the tunes are reprised, but only one to any theatrical effect: “Masquerade” opens the Second Act as a splashy production number, then returns at the end as a poignant solo for Michael Crawford (as the Phantom). The other themes recur with different lyrics, which reflect no credit on their writers, Charles Hart and Richard Stilgoe. When a melody has six sets of words, it usually means none of them are right. “Hey, Big Spender”, for example, says what the music says, and nobody would dream of reprising it as “When’s The Mail Due?” or “How’s Your Meatloaf?”. And when a tune can be sung by any of the principal characters (as most of Phantom’s are), it also indicates something is wrong: try swapping Eliza’s and Professor Higgins’ and see if My Fair Lady still makes sense.

Oscar Hammerstein wrote warm, tender songs, stuffed with precise images: as Goethe put it, the poet should write about the specific and, if he is any good, he will express the universal. These lyrics are bland, vague, worthier of a Victor Herbert or Franz Lehar score: “soon you’ll be beside me/you’ll guard me and you’ll guide me”. Elsewhere, Lloyd Webber’s often attractive melodies have their impact diminished by being perversely under-rhymed, while the solitary comic number is obtrusively over-rhymed and yet remains resolutely unfunny...

In other areas, though, “Phantom” has much to be admired. Maria Bjöernson, the designer, has imbued the Opera House with an authentically musty, cobwebbed atmosphere. Sarah Brightman makes an irresistible heroine. The text does not provide her with much, but a combination of sheer gusto, ethereal top notes and those Jessie Matthews eyes sees her through, She hams it up splendidly as the principal boy in the mock opera Il Muto . Michael Crawford, the West End’s outstanding musical actor, is shamefully underused here, al though what he does he does well.

The musical opens with a spoken prologue, an innovation which the rest of the show fails to live up to. Starlight Express brought the form to the edge of the abyss; The Phantom of the Opera takes it back a few yards, but we're not out of the danger zone yet...

___________

The Phantom of the Opera

Her Majesty's, London

Michael Billington for The Guardian

Saturday October 11, 1986

We have had some pretty grim experiences in musical theatre in recent years. We have seen people turned into roller-skating ciphers, dwarfed by laser-beams and sententious holograms and treated as pawns in political chess-games. But the cheering thing about The Phantom Of The Opera is that it puts spectacle (and there is plenty of it) to the service of an exciting story and in that music is used, in a Pucciniesque way to intensify a dramatic situation.

Andrew Lloyd Webber and Richard Stilgoe, responsible for the book, have had the shrewd idea of going back to Gaston Leroux's original 1911 novel. So we get a story that mixes horror and romance in equal proportions: horror in that it is about the terrorisation of the Paris Opera House by an elusive phantom who causes multiple deaths when his demands are not met, romance in that it is a Beauty and the Beast myth about a disfigured hero who can only express his love for a soprano by becoming her musical inspiration.

It may be hokum but it is hokum here treated with hand on heart rather than tongue in cheek. And even if one misses some of Leroux's grislier details, such as the final incarceration of the soprano's rescue in a hexagonal, water-filled torture-chamber, the palpable sincerity means that there is never any danger of The Phantom Of The Opera becoming like the Marx Brother's Night At The Opera.

We are made to care about the people (though Raoul, the romantic rescuer, seems a bit wimpy compared to the figure of purbind obstinacy Leroux created). But much of the success of the evening lies in Lloyd Webber's ability to move from operatic pastiche to music full of plangent yearning.

Resisting the temptation to use lashings of Gounod, he gives us a mixture of Metro-Goldwyn Meyerbeer, cod-Mozart and, in the Phantom's own Don Juan opera, something that is 1860s avant-garde. Lloyd Webber's own prevailing style, however, is lush, romantic, string-filled and, if occasionally one achingly passionate number threatens to merge into another, the effect is offset by the comic jauntiness of Prima Donna or the pavane-like stateliness of Masquerade with neat lyrics ('Masquerade-paper faces on parade,') by Charles Hart.

This last number is one of many whose effect is heightened by the masterly direction of Harold Prince and designs of Maria Bjornson. The occasion is a New Year's Eve Masked Ball at the Opera House and a grand sweeping staircase (Ms Bjornson is very fond of staircases) is filled with a kaleidoscopic harlequinade which suddenly parts to reveal the Phantom who has come as the Red Death. It is a powerful moment and it exemplifies the consistent delight in theatricality.

Prince and Bjornson throughout stress the sinister opulence of the Paris Opera with heavy, swagged curtains, bulging, gilt caryatids and, most spectacularly, a descent into the underworld via a tilting bridge that leads to a candle-filled lake reminiscent of one of mad Ludwig's Bavarian castles. And if the famous chandelier's ascent was slightly more exciting than its ultimate descent that was because we all know that what goes up must come down.

But Prince has caught the feverish, nightmarish bustle of Leroux's Opera House without diminishing the people. Michael Crawford as the Phantom, above all, brings out the character's solitary pathos rather than his demonic horror: it is the humanity under the mask that seizes the attention, not least when his flickering, desperate hands suddenly emerge from behind an Angel of Music hovering over the lovers on the Opera House rooftop.

Sarah Brighman sings sweetly and prettily as Christine without quite suggesting she'd be the overnight toast of Paris. And even if Steve Barton can't do much with the underwritten Raoul, there is strong support from Rosemary Ashe as the displaced prima donna whose voice suddenly turns to a frog-croak and from John Savident as a comically officious Opera House manager.

In the end The Phantom works, despite the odd blank stretch, because it delights in the possibilities of theatre: from a vast prop elephant (operated by beer-swilling stagehands) to the demonking disappearance of its hero through the floor-surface. It is determinedly old-fashioned but when the new fashion is for boy-meets-laser-beam, it is refreshing to find a musical that pins its faith in people, narrative and traditional illusion.

_______________

A Monster-Meets-Girl Romance

WILLIAM A. HENRY III reviews The Phantom of the Opera in London for TIME magazine, Oct. 27, 1986

As the copyright on Gaston Leroux's 1911 thriller The Phantom of the Opera expired this year, plans were announced for no fewer than three competing musical adaptations. The flurry of interest was perplexing. Leroux's tale, part horror melodrama, part bodice-ripping gothic, seemed too grim and kinky for a musical. The central character is, after all, not only hideously ugly but an extortionist, kidnaper, incendiary and megalomaniac -- and the heroine must at least halfway fall in love with him.

The winners of the race to stage a Phantom in a major commercial setting, Composer Andrew Lloyd Webber and Director Harold Prince, have proved the shrewdness of their unlikely impulse. Within two days after the $3 million spectacular opened in London's West End this month, the box office was virtually sold out until early 1987. Webber and Prince have daringly envisioned Phantom not as Grand Guignol but as an opportunity to turn the musical back toward what they term romance. Ironically, Lloyd Webber (Evita) and Prince (Sweeney Todd) have been leaders in the movement to push musicals beyond traditional boy-meets-girl accessibility. Yet their Phantom is unquestionably a love story, just as much for the heroine, a baffled girl from the chorus, as for the masked enigma who spirits her down to the labyrinthine bowels of the Paris Opera House to teach her to become a star.

It is often said of Lloyd Webber's musicals that the show is the star, and of Prince's stagings that the director is the star. Both dicta might apply to Phantom, which is opulently costumed, lushly scored, full of spectacular stage pictures and chockablock with pastiches of 19th century warhorse opera. But in the midst of all the mechanics there are 2 1/2 performances that achieve some emotional depth. Michael Crawford commands the stage as the Phantom, bringing complete conviction to such fantasies as a midair descent on a chariot of gilded cherubs and a boating trip on a subterranean lake dotted with candelabra. As his alternately terrified and thrilled disciple, Sarah Brightman is more singer than actress but still manages to suggest a neurasthenic obsession with the Phantom. The half performance comes from erstwhile Ballet Dancer Steve Barton, who looks good and sings well as Christine's real-world lover but is unable to bring much color to the role.

Musically Phantom is at once more sophisticated and less hummably memorable than most of Lloyd Webber's shows. There is no song to compare with Memory in Cats. Instead there are sequences that verge on opera, the most ambitious being a quasi-Mozartian septet. Unfortunately, the wit and scholarship of his tunes are nowhere echoed in Hart's lyrics, which oscillate between the banal and the impenetrable.

The show's most serious shortcoming is its scant supply of sentiment. Because the narrative hurtles immediately into action, it takes quite a while to involve the audience with the characters. Then, just when it has developed the Phantom as a pathetic blend of noble genius and physical freak, it turns him into an almost random murderer. In an ideal entertainment, there must be someone to root for. But as Alice noted of a wonderland no more demented or enchanted than the Phantom's opera house, they are all very unpleasant people here.

________

If anyone here can post other reviews for the London production, particularly John Barber's one for The Daily Telegraph, plus the ones for papers like The Evening Standard, I'd be grateful!

God's gift to musical theatre

by Irving Wardle

The Phantom of the Opera

Her Majesty's

One thing is clear: Gaston Leroux's famous story is God's gift to musical theatre. It wraps up the legends of Faust, Svengali, and Beauty and the Beast into a grand final death rattle of the romantic agony. It turns a theatre -- the Paris Opera -- into a replica of the universe, from the Statue of Apollo above the city's rooftops down to the infernal regions with their furnaces and stygian lake. And, musically, not only does it unfold to an accompaniment of the operatic repertoire, but also features a protagonist who is himself a great composer.

Some of these opportunities have been seized by Andrew Lloyd Webber and his collaborators, and projected with stunning showmanship in Harold Prince's production. But their full range has been much restricted by the decision to present the events above all as a tragic love story.

That indeed is the mainspring of Leroux's plot in which the hideously deformed Erik, hiding in the catacombs of the theatre, conceives a desperate passion for the young soprano, Christine, teaches her to sing like an angel, and then spirits her away to his lair when an aristocratic rival -- the gallant young Raoul -- appears on the scene. But Erik is also a prankster in the ETA-Hoffmann traditional and much of the story's vitality depends on the jokes he plays on the opera's employees and its wretched managers.

The musical opens with an auction, long after the events, showing the aged Raoul snapping up mementos of his youthful romance -- rather along the lines of Zeffirelli's posthumous prelude to Traviata. That sets the sombre tone of the evening. And after a brisk rehearsal scene, showing the coryphees and the vastly self-satisfied lead singers battling through an old war-horse called Hannibal, with a full-scale elephant, romance closes in. Raoul pursues Christine to her dressing room where he is overheard by the Phantom, who promptly materializes through the magic mirror and leads her down to his house by the lake.

This is the biggest miscalculation in Richard Stilgoe's book: as it reveals the Phantom as a man from the start instead of springing that disclosure after a succession of seemingly supernatural incidents. As a result, there is precious little thrill in hearing his disembodied voice or witnessing his apparition as the Mask of Red Death at the company's masquerade party. Nor do we ever learn how he performs his tricks. Instead of revealing them as the work of a master ventriloquist and conjurer, they remain unexplained mysteries somehow performed by a man whose only visible skill is to crash out dischords on his subterranean harmoninium.

Elsewhere, Mr Stilgoe has worked wonders of dramatic compression: creating the intensely sinister figure of a ballet mistress (Mary Millar) who acts as a stone-faced messenger between the Phantom and his victims; and reconstructing the disruption of a performance by breaking up a balletic entra'racte with the descent of a hanged man from the flies. I suspect, though, that the sharp-witted Mr Stilgoe was not the man for the love lyrics; which have been produced in saccharin abundance by Charles Hart. This may be the kind of material Lloyd Webber wanted to set; but as both lovers approach Christine on similar terms, offering comfort, warmth, and protection, a monotony sets in well before the Phantom yields to the better man and vanishes into a trick piece of furniture.

The book, however, has much more importance than in his previous work; and this time the score is not through-composed in a continuous idiom. Instead it moves between 19th century opera (discarding Leroux's Faust in favour of risible pastiche), atmospheric and love music in his own lucious vein, and the compositions of the ghost himself. The power of the score depends much more on contrast than on any individual item. Lullaby like romantic numbers are poisoned by menacingly surging undercurrents. These turn out only to be descending chromatic scales on the brass, but they serve their turn. When it comes to rehearsing the ghost's own opera (another Stilgoe innovation) it is great fun to discover that tenor lead cannot get the hang of whole-tone scales. Elsewhere the presence of the supernatural is expressively signalled by unrelated minor chords descending in parallel like the endless trapdoors leading down to the cellars of the theatre.

One thing the production should do is to confirm the vocal powers of Sarah Brightman, a blanched victim with huge panic-striken eyes, who combines a honeyed middle register with the unearthly top notes I first thrilled to when she sang Charles Strouse's Nightingale. Michael Crawford as the Phantom is a worthy vocal partner, but it is a pity that he should have such small opportunity to display his other skills.

___________

It’s fantastic, fabulous and phantasmagorical!

John Blake, Daily Mirror, 10th October 1986

It's fantastic, fabulous and phantasmagorical! From the eerily flickering lights that greet you outside Her Majesty's Theatre to the last, glorious curtain call, Andrew Lloyd Webber's long-awaited new musical, Phantom of the Opera, is a triumph.

The special effects are among the most spectacular ever seen in the West End.

The music is every bit as memorable as one would expect from the man who wrote Evita, Starlight Express and the rest. But most of all, the show belongs to Sarah Brightman and Michael Crawford, who soar and swoop through their hugely demanding roles like eagles.

After all the well-publicised false starts and back-biting, Lloyd Webber has created a musical which deserves to be around well into the next decade.

The story is based closely on the original novel of 1911 - unlike most of the Phantom of the Opera films which have been made over the years.

Michael Carwford's Phantom hides his hideously disfigured face by skulking in the stage caverns and pools deep beneath the Paris opera.

His passion for music is the only thing which gives his life meaning until he becomes obsessed by Sarah Brightman's Christine - a young opera singer whose beauty is matched only by the purity of her voice. He coaches her in secret while visiting dreadful catastrophes on anyone who refuses to advance her career.

A hanged scene shifter is suddenly hideously dropped on to the stage in the middle of a performance. A vast crystal chandelier crashes on to the audience.

As the phantom becomes more fiendish so Christine becomes increasingly mixed in her feelings towards him.

A dreadful climax is fast approaching.

The eerie sets of the unfolding drama - great stages filled with mist and shining candles - are interspersed with all the colour and spectacle of the operas being prepared and presented at the theatre.

Despite all the "ghost train" theatricals the greatest thrills of the show come from Michael Crawford.

He not only sings superbly but also captures the torment of the Phantom perfectly.

If you only see one show this year, make sure it is this one!

_____________

Jack Tinker, Daily Mail, 10th October 1986

Four words sum up the unstoppable success of Andrew Lloyd Webber's triumphant re-working of this vintage spine-tingling melodrama. Stars, spectacle, score and story.

Together they add up to that old magic ingredient: theatricality. There is simply nothing on earth to transport you so quickly or so far into phantasy than a feast of illusions. And Hal Prince's production stints nothing in providing an unending banquet of the stuff.

When I get my breath back from gulping down as much as is decent in one sitting, let me deal with each item in turn.

First the star and the evening's greatest surprise. Were it not that I personally know Michael Crawford's singing teacher to be the kindest and mildest of men, I would swear that Mr Crawford had sold his soul to the Devil to acquire the rich and powerful voice with which he floods the theatre and holds us hypnotised in his presence.

The mask that for most of the evening obliterates half his face only hints at the physical horrors beneath it. But, by the time his golden-voiced protégé has torn it aside to reveal a peeling skull and rotting flesh, he has utterly established the phantom as one of the enduring tragic figures of the modern musical; a man with a tender, gifted and loving soul whose only crime was to have been born a freak.

It is surely one of the great performances, not only in a musical but on any stage and in any year.

In this Mr Crawford is indeed fortunate to be partnered by someone as illustrious and exotically voiced as Sarah Brightman. I can think of no other actress whose glorious operatice range can match a stage present so delicately vulnerable or exquisitely beautiful.

On now to the full throttle spectacle that Maria Bjornson has conjured up to encompass all the diverse elements of the evening.

Giant chandeliers plummet from on high; great gilded angels bear Mr Crawford skyward as he sings out his heart to heaven; a lavish fancy dress masquerade underlines the sinister nature of disguise; high-camp pastiches of less than grand opera strike just the right note of comic relief while a lake of lights floats us down to the Phantom's lair beneath the great Opera House of Paris.

As for the score, it soars and instils itself into the mind like some half-forgotten refrain from Verdi, taking the story line on in great sweeps of musical sound. In its unabashed romanticism it reminds us that the Phantom is at heart a simple take of unrequited love, as inspiring and moving it its way as Romeo and Juliet, or more appropriately Beauty and the Beast.

Yet to underline the sheer theatricality of the piece the Phantom does nothing so mundane as to die for love. He vanishes in a blink before our eyes.

True there are faults but to pick them here and now would be churlish and irrelevant. Mr Lloyd Webber has another long-term tenancy and his wife has established herself as a star of status.

As for Michael Crawford there is just no other artist in the country today who can touch his command of a stage or match his daring in meeting a new challenge.

______

Richard Barkley, Sunday Express, 12th October 1986

Andrew Lloyd Webber's new musical The Phantom of The Opera is a gorgeous operatic extravaganza that is a thrill to the blood and a sensual feast for the eye.

High melodrama is the key note from the start when the rich splendours of a rehearsal at the Paris Opera of Hannibal, complete with slave girls and elephant, is brought shiveringly short by the ghostly intervention of the phantom.

As warning blasts of brass from the 27-piece orchestra trigger our apprehension, the half-masked phantom appears behind chorus girl Christine's mirror to lure her down through a labyrinth to the candle-lit intimacy of his subterranean world.

Using subtle vocal intonation and body movement in an extraordinarily moving performance, an almost unrecognisable Michael Crawford devastates us with the anguish and despair of the phantom, a freak ultimately failing in his struggle to overcome the disfiguring mistake of nature that has rendered him unloved since birth.

Sarah Brightman's wide-eyed beauty and soaring soprano voice make something individual and touching out of Christine's tussle between pity for the phantom and love for her friend and admirer, the Vicomte de Chagny (Steve Barton).

It is a lyrical high point when she expresses her sympathy for the phantom in Wishing You Were Somehow Here Again, a melody that carries an eerie echo of the Pie Jesu from Lloyd Webber's Requiem.

Meanwhile the evening, rooted in the Gaston Leroux novel, dispenses a great rolling buffet of musical delights.

And there is one particularly striking set piece stage by Gillian Lynne under Harold Prince's direction as the huge drapes fall back to reveal the company poised on the Opera's grad staircase for a masked ball, which is performed to the seductive syncopation of a bolero-like rhythm.

But as you rock back in your seat from sudden sunbursts of light, the reek of gunpowder and the impact of a chandelier crashing from the roof above the stalls to the stage, Michael Crawford's magnificent performance permeates all to produce a dramatic unity ultimately aching with pathos.

_________

Mark Steyn writing for The Independent, October 11 1986

Thirty years ago, Damn Yankees , produced by Harold Prince, articulated the first rule of musical theatre: “You gotta have Heart”, sage advice which both Prince and Andrew Lloyd Webber, now re-united as director and composer of The Phantom of the Opera, have on occasion chosen to ignore. Gaston Leroux’s 1911 novel, however, has the key ingredient in spades. A confused heroine is torn between a handsome aristocrat and a misunderstood misfit who haunts the Paris Opéra - real emotion, a world away from Starlight Express and co. Indeed, in one of Phantom ’s “opera-within-an-opera” scenes, Prince manages a sly dig at the technological gimmick shows by bringing on a giant elephant, inside of which two bored stage-hands are playing cards. Unlike Time and Mutiny, where it diverts attention from the inadequacies of the drama, the technology here (a crashing chandelier, a lake) actually services the show.

Lloyd Webber has described Phantom as a return to the values of Rodgers and Hammerstein, and at moments his rich, soaring melodies are worthy of either Rodgers or Kern at their most lyrical (although “Angel Of Music” struck me as reminiscent of the middle section in Sondheim’s “Not While I’m Around” and, blow me, as I stumbled out into the Haymarket, that’s exactly what a fellow first-nighter was singing). The score, however, Is dreadfully unbalanced. For every “Some Enchanted Evening”, Rodgers had a "Nothin' Like A Dame”. Here, the only upbeat number is the forceful title song, which serves as a very heavy leitmotif.

Most of the tunes are reprised, but only one to any theatrical effect: “Masquerade” opens the Second Act as a splashy production number, then returns at the end as a poignant solo for Michael Crawford (as the Phantom). The other themes recur with different lyrics, which reflect no credit on their writers, Charles Hart and Richard Stilgoe. When a melody has six sets of words, it usually means none of them are right. “Hey, Big Spender”, for example, says what the music says, and nobody would dream of reprising it as “When’s The Mail Due?” or “How’s Your Meatloaf?”. And when a tune can be sung by any of the principal characters (as most of Phantom’s are), it also indicates something is wrong: try swapping Eliza’s and Professor Higgins’ and see if My Fair Lady still makes sense.

Oscar Hammerstein wrote warm, tender songs, stuffed with precise images: as Goethe put it, the poet should write about the specific and, if he is any good, he will express the universal. These lyrics are bland, vague, worthier of a Victor Herbert or Franz Lehar score: “soon you’ll be beside me/you’ll guard me and you’ll guide me”. Elsewhere, Lloyd Webber’s often attractive melodies have their impact diminished by being perversely under-rhymed, while the solitary comic number is obtrusively over-rhymed and yet remains resolutely unfunny...

In other areas, though, “Phantom” has much to be admired. Maria Bjöernson, the designer, has imbued the Opera House with an authentically musty, cobwebbed atmosphere. Sarah Brightman makes an irresistible heroine. The text does not provide her with much, but a combination of sheer gusto, ethereal top notes and those Jessie Matthews eyes sees her through, She hams it up splendidly as the principal boy in the mock opera Il Muto . Michael Crawford, the West End’s outstanding musical actor, is shamefully underused here, al though what he does he does well.

The musical opens with a spoken prologue, an innovation which the rest of the show fails to live up to. Starlight Express brought the form to the edge of the abyss; The Phantom of the Opera takes it back a few yards, but we're not out of the danger zone yet...

___________

The Phantom of the Opera

Her Majesty's, London

Michael Billington for The Guardian

Saturday October 11, 1986

We have had some pretty grim experiences in musical theatre in recent years. We have seen people turned into roller-skating ciphers, dwarfed by laser-beams and sententious holograms and treated as pawns in political chess-games. But the cheering thing about The Phantom Of The Opera is that it puts spectacle (and there is plenty of it) to the service of an exciting story and in that music is used, in a Pucciniesque way to intensify a dramatic situation.

Andrew Lloyd Webber and Richard Stilgoe, responsible for the book, have had the shrewd idea of going back to Gaston Leroux's original 1911 novel. So we get a story that mixes horror and romance in equal proportions: horror in that it is about the terrorisation of the Paris Opera House by an elusive phantom who causes multiple deaths when his demands are not met, romance in that it is a Beauty and the Beast myth about a disfigured hero who can only express his love for a soprano by becoming her musical inspiration.

It may be hokum but it is hokum here treated with hand on heart rather than tongue in cheek. And even if one misses some of Leroux's grislier details, such as the final incarceration of the soprano's rescue in a hexagonal, water-filled torture-chamber, the palpable sincerity means that there is never any danger of The Phantom Of The Opera becoming like the Marx Brother's Night At The Opera.

We are made to care about the people (though Raoul, the romantic rescuer, seems a bit wimpy compared to the figure of purbind obstinacy Leroux created). But much of the success of the evening lies in Lloyd Webber's ability to move from operatic pastiche to music full of plangent yearning.

Resisting the temptation to use lashings of Gounod, he gives us a mixture of Metro-Goldwyn Meyerbeer, cod-Mozart and, in the Phantom's own Don Juan opera, something that is 1860s avant-garde. Lloyd Webber's own prevailing style, however, is lush, romantic, string-filled and, if occasionally one achingly passionate number threatens to merge into another, the effect is offset by the comic jauntiness of Prima Donna or the pavane-like stateliness of Masquerade with neat lyrics ('Masquerade-paper faces on parade,') by Charles Hart.

This last number is one of many whose effect is heightened by the masterly direction of Harold Prince and designs of Maria Bjornson. The occasion is a New Year's Eve Masked Ball at the Opera House and a grand sweeping staircase (Ms Bjornson is very fond of staircases) is filled with a kaleidoscopic harlequinade which suddenly parts to reveal the Phantom who has come as the Red Death. It is a powerful moment and it exemplifies the consistent delight in theatricality.

Prince and Bjornson throughout stress the sinister opulence of the Paris Opera with heavy, swagged curtains, bulging, gilt caryatids and, most spectacularly, a descent into the underworld via a tilting bridge that leads to a candle-filled lake reminiscent of one of mad Ludwig's Bavarian castles. And if the famous chandelier's ascent was slightly more exciting than its ultimate descent that was because we all know that what goes up must come down.

But Prince has caught the feverish, nightmarish bustle of Leroux's Opera House without diminishing the people. Michael Crawford as the Phantom, above all, brings out the character's solitary pathos rather than his demonic horror: it is the humanity under the mask that seizes the attention, not least when his flickering, desperate hands suddenly emerge from behind an Angel of Music hovering over the lovers on the Opera House rooftop.

Sarah Brighman sings sweetly and prettily as Christine without quite suggesting she'd be the overnight toast of Paris. And even if Steve Barton can't do much with the underwritten Raoul, there is strong support from Rosemary Ashe as the displaced prima donna whose voice suddenly turns to a frog-croak and from John Savident as a comically officious Opera House manager.

In the end The Phantom works, despite the odd blank stretch, because it delights in the possibilities of theatre: from a vast prop elephant (operated by beer-swilling stagehands) to the demonking disappearance of its hero through the floor-surface. It is determinedly old-fashioned but when the new fashion is for boy-meets-laser-beam, it is refreshing to find a musical that pins its faith in people, narrative and traditional illusion.

_______________

A Monster-Meets-Girl Romance

WILLIAM A. HENRY III reviews The Phantom of the Opera in London for TIME magazine, Oct. 27, 1986

As the copyright on Gaston Leroux's 1911 thriller The Phantom of the Opera expired this year, plans were announced for no fewer than three competing musical adaptations. The flurry of interest was perplexing. Leroux's tale, part horror melodrama, part bodice-ripping gothic, seemed too grim and kinky for a musical. The central character is, after all, not only hideously ugly but an extortionist, kidnaper, incendiary and megalomaniac -- and the heroine must at least halfway fall in love with him.

The winners of the race to stage a Phantom in a major commercial setting, Composer Andrew Lloyd Webber and Director Harold Prince, have proved the shrewdness of their unlikely impulse. Within two days after the $3 million spectacular opened in London's West End this month, the box office was virtually sold out until early 1987. Webber and Prince have daringly envisioned Phantom not as Grand Guignol but as an opportunity to turn the musical back toward what they term romance. Ironically, Lloyd Webber (Evita) and Prince (Sweeney Todd) have been leaders in the movement to push musicals beyond traditional boy-meets-girl accessibility. Yet their Phantom is unquestionably a love story, just as much for the heroine, a baffled girl from the chorus, as for the masked enigma who spirits her down to the labyrinthine bowels of the Paris Opera House to teach her to become a star.

It is often said of Lloyd Webber's musicals that the show is the star, and of Prince's stagings that the director is the star. Both dicta might apply to Phantom, which is opulently costumed, lushly scored, full of spectacular stage pictures and chockablock with pastiches of 19th century warhorse opera. But in the midst of all the mechanics there are 2 1/2 performances that achieve some emotional depth. Michael Crawford commands the stage as the Phantom, bringing complete conviction to such fantasies as a midair descent on a chariot of gilded cherubs and a boating trip on a subterranean lake dotted with candelabra. As his alternately terrified and thrilled disciple, Sarah Brightman is more singer than actress but still manages to suggest a neurasthenic obsession with the Phantom. The half performance comes from erstwhile Ballet Dancer Steve Barton, who looks good and sings well as Christine's real-world lover but is unable to bring much color to the role.

Musically Phantom is at once more sophisticated and less hummably memorable than most of Lloyd Webber's shows. There is no song to compare with Memory in Cats. Instead there are sequences that verge on opera, the most ambitious being a quasi-Mozartian septet. Unfortunately, the wit and scholarship of his tunes are nowhere echoed in Hart's lyrics, which oscillate between the banal and the impenetrable.

The show's most serious shortcoming is its scant supply of sentiment. Because the narrative hurtles immediately into action, it takes quite a while to involve the audience with the characters. Then, just when it has developed the Phantom as a pathetic blend of noble genius and physical freak, it turns him into an almost random murderer. In an ideal entertainment, there must be someone to root for. But as Alice noted of a wonderland no more demented or enchanted than the Phantom's opera house, they are all very unpleasant people here.

________

If anyone here can post other reviews for the London production, particularly John Barber's one for The Daily Telegraph, plus the ones for papers like The Evening Standard, I'd be grateful!

Broadway reviews 1988

Broadway reviews 1988

"Phantom of the Opera"

By FRANK RICH for the NEW YORK TIMES

Jan. 27, 1988

It may be possible to have a terrible time at "The Phantom of the Opera," but you'll have to work at it. Only a terminal prig would let the avalanche of pre-opening publicity poison his enjoyment of this show, which usually wants nothing more than to shower the audience with fantasy and fun, and which often succeeds, at any price.

It would be equally ludicrous, however --- and an invitation to severe disappointment --- to let the hype kindle the hope that "Phantom" is a credible heir to the Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals that haunt both Andrew Lloyd Webber's creative aspirations and the Majestic Theater as persistently as the evening's title character does.

What one finds instead is a characteristic Lloyd Webber project -- long on pop professionalism and melody, impoverished of artistic personality and passion -- that the director Harold Prince, the designer Maria Bjornson and the mesmerizing actor Michael Crawford have elevated quite literally to the roof. "The Phantom of the Opera" is as much a victory of dynamic stagecraft over musical kitsch as it is a triumph of merchandising uber alles.

As you've no doubt heard, "Phantom" is Mr. Lloyd Webber's first sustained effort at writing an old-fashioned romance between people instead of cats or trains. The putative lovers are the Paris Opera House phantom (Mr. Crawford) and a chorus singer named Christine Daae (Sarah Brightman). But Mr. Crawford's moving portrayal of the hero notwithstanding, the show's most persuasive love story is Mr. Prince's and Ms. Bjornson's unabashed crush on the theater itself, from footlights to dressing rooms, from flies to trap doors.

A gothic backstage melodrama, "Phantom" taps right into the obsessions of the designer and the director. At the Royal Shakespeare Company, Ms. Bjornson was a wizard of darkness, monochromatic palettes and mysterious grand staircases.

Mr. Prince, a prince of darkness in his own right, is the master of the towering bridge ("Evita"), the labyrinthine inferno ("Sweeney Todd") and the musical-within-the-musical ("Follies").

In "Phantom," the creative personalities of these two artists merge with a literal lightning flash at the opening coup de theatre, in which the auditorium is transformed from gray decrepitude to the gold-and-crystal Second Empire glory of the Paris Opera House.

Though the sequence retreads the famous Ziegfeld palace metamorphosis in "Follies," Ms. Bjornson's magical eye has allowed Mr. Prince to reinvent it, with electrifying showmanship. The physical production, Andrew Bridge's velvety lighting included, is a tour de force throughout -- as extravagant of imagination as of budget.

Ms. Bjornson drapes the stage with layers of Victorian theatrical curtains -- heavily tasseled front curtains, fire curtains, backdrops of all antiquated styles -- and then constantly shuffles their configurations so we may view the opera house's stage from the perspective of its audience, the performers or the wings.

For an added lift, we visit the opera-house roof, with its cloud-swept view of a twinkling late-night Paris, and the subterreanean lake where the Phantom travels by gondola to a baroque secret lair that could pass for the lobby of Grauman's Chinese Theater. The lake, awash in dry-ice fog and illuminated by dozens of candelabra, is a masterpiece of campy phallic Hollywood iconography -- it's Liberace's vision of hell.

There are horror-movie special effects, too, each elegantly staged and unerringly paced by Mr. Prince. The imagery is so voluptuous that one can happily overlook the fact that the book (by the composer and Richard Stilgoe) contains only slightly more plot than "Cats," with scant tension or suspense. This "Phantom," more skeletal but not briefer than other adaptations of the 1911 Gaston Leroux novel, is simply a beast-meets-beauty, loses-beauty story, attenuated by the digressions of disposable secondary characters (the liveliest being Judy Kaye's oft-humiliated diva) and by Mr. Lloyd Webber's unchecked penchant for forcing the show to cool its heels while he hawks his wares.

In Act II, the heroine travels to her father's grave for no reason other than to sell an extraneous ballad whose tepid greeting-card sentiments ("Wishing You Were Somehow Here Again") dispel the evening's smoldering mood. The musical's dramatic thrust is further slowed by three self-indulgently windy opera parodies -- in which the sophisticated tongue-in-cheek wit of Ms. Bjornson's sumptuous period sets and costumes is in no way matched by Gillian Lynne's repetitive, presumably satirical ballet choreography or by Mr. Lloyd Webber's tiresome collegiate jokes at the expense of such less than riotous targets as Meyerbeer.

Aside from the stunts and set changes, the evening's histrionic peaks are Mr. Crawford's entrances -- one of which is the slender excuse for Ms. Bjornson's most dazzling display of Technicolor splendor, the masked ball ("Masquerade") that opens Act II.

Mr. Crawford's appearances are eagerly anticipated, not because he's really scary but because his acting gives "Phantom" most of what emotional heat it has. His face obscured by a half-mask -- no minor impediment -- Mr. Crawford uses a booming, expressive voice and sensuous hands to convey his desire for Christine.

His Act I declaration of love, "The Music of the Night" -- in which the Phantom calls on his musical prowess to bewitch the heroine -- proves as much a rape as a seduction.

Stripped of the mask an act later to wither into a crestfallen, sweaty, cadaverous misfit, he makes a pitiful sight while clutching his beloved's discarded wedding veil.

Those who visit the Majestic expecting only to applaud a chandelier -- or who have 20-year-old impressions of Mr. Crawford as the lightweight screen juvenile of "The Knack" and "Hello, Dolly!" -- will be stunned by the force of his Phantom.

It's deflating that the other constituents of the story's love triangle don't reciprocate his romantic or sexual energy. The icily attractive Ms. Brightman possesses a lush soprano by Broadway standards (at least as amplified), but reveals little competence as an actress. After months of playing "Phantom" in London, she still simulates fear and affection alike by screwing her face into bug-eyed, chipmunk-cheeked poses more appropriate to the Lon Chaney film version.

Steve Barton, as the Vicomte who lures her from the beast, is an affable professional escort with unconvincingly bright hair.

Thanks to the uniform strength of the voices -- and the soaring, Robert Russell Bennett-style orchestrations -- Mr. Lloyd Webber's music is given every chance to impress.

There are some lovely tunes, arguably his best yet, and, as always, they are recycled endlessly: if you don't leave the theater humming the songs, you've got a hearing disability. But the banal lyrics, by Charles Hart and Mr. Stilgoe, prevent the score's prettiest music from taking wing. The melodies don't find shape as theater songs that might touch us by giving voice to the feelings or actions of specific characters.

Instead, we get numbing, interchangeable pseudo-Hammersteinisms like "Say you'll love me every waking moment" or "Think of me, think of me fondly, when we say goodbye."

With the exception of "Music of the Night" -- which seems to express from its author's gut a desperate longing for acceptance -- Mr. Lloyd Webber has again written a score so generic that most of the songs could be reordered and redistributed among the characters (indeed, among other Lloyd Webber musicals) without altering the show's story or meaning. The one attempt at highbrow composing, a noisy and gratuitous septet called "Prima Donna," is unlikely to take a place beside the similar Broadway operatics of Bernstein, Sondheim or Loesser.

Yet for now, if not forever, Mr. Lloyd Webber is a genuine phenomenon -- not an invention of the press or ticket scalpers -- and "Phantom" is worth seeing not only for its punch as high-gloss entertainment but also as a fascinating key to what the phenomenon is about.

Mr. Lloyd Webber's esthetic has never been more baldly stated than in this show, which favors the decorative trappings of art over the troublesome substance of culture and finds more eroticism in rococo opulence and conspicuous consumption than in love or sex.

Mr. Lloyd Webber is a creature, perhaps even a prisoner, of his time; with "The Phantom of the Opera," he remakes La Belle Epoque in the image of our own Gilded Age. If by any chance this musical doesn't prove Mr. Lloyd Webber's most popular, it won't be his fault, but another sign that times are changing and that our boom era, like the opera house's chandelier, is poised to go bust.

________________________

Newsday's 1988 "Phantom" review

Manifold Delights in the `Phantom'

By Allan Wallach

January 27, 1988

`THE PHANTOM of the Opera" is sold out so far into the future that people may one day be declaring their all-but-unobtainable tickets in wills and divorce settlements. So it's largely to comfort those who have already purchased their tickets rather than to discomfort those who delayed that I report that the Andrew Lloyd Webber musical is every bit as stunning on Broadway as in London.

Why this show makes so overwhelming an impact takes a little explaining. The story, after all, is drawn from a novel by a minor French novelist that's been around, largely unread, since 1911. And while Lloyd Webber's music has a lush, romantic sweep, so does that of many operas that don't compel such astonishing attention.

The triumph of "The Phantom of the Opera" lies in the amalgam of virtually all its elements into as gloriously theatrical a show as we've had in recent memory. They coalesce into a musical of manifold delights: Harold Prince's virtuoso direction, the performances led by Michael Crawford and Sarah Brightman, the spectacle created by a brilliant design team, the beautifully sung music and Gillian Lynne's period choreography.

But yes, there are some faults. For me, after seeing the show in its London and New York productions and listening to the London cast album, Lloyd Webber's music has some problematical aspects. Though I think it is the finest of his career, he has relied excessively on a few musical motifs for the central characters. And Charles Hart's lyrics fall far short of sophisticated, even for a melodramatic story such as this one.

It's the totality, though, that matters. "Phantom," like Lloyd Webber's "Cats," succeeds by establishing a special milieu - a world where, once willingly entered, we surrender to a story that might seem ludicrous in a less evocative context.

That world is the Paris Opera House during la Belle Epoque. Gaston Leroux, author of the novel that became the basis for so many varied treatments, drew upon the fact that beneath the opera house were a honeycomb of passages and a lake, and that a chandelier counterweight had once fallen on the audience. These things are central to his story of a horribly disfigured Phantom, a masked "opera ghost" who tyrannizes all who work at the opera and is himself the slave of a hopeless love for the young singer Christine Daae. Casting a mesmeric spell, he is the Svengali to her Trilby, the Beast to her Beauty.

The book by Richard Stilgoe and Lloyd Webber, differing in some particulars from the novel and the famous 1925 silent film, gives the affair an erotic undertow, an overripe mood of sexual repression and decay that is deepened by Lloyd Webber's seductive melodies. This is his most operatic score to date, both because of his Puccini-scented music for the blighted romance and the opera pastiches incorporated elsewhere.

Giving a performance likely to be remembered for decades, Crawford is extraordinary as the Phantom. It would be hard to imagine the musical without his magnetic presence and eerie tenor, without the poignantly broken figure he becomes. Brightman, possessed of a lovely soprano and fragile beauty, is an ideal Christine. (The musical, however, was equally compelling when I saw it in London with an unknown replacement, and I'm sure those who see the talented Patti Cohenour at certain performances will not be shortchanged.)

In the largely recast production, the most effective work is done by Steve Barton as the young aristocrat who loves Christine, Cris Groenendaal as an impresario, Elisa Heinsohn as a dancer and Leila Martin as her mysterious mother. I wasn't taken with Judy Kaye's campy performance as the reigning diva whom Christine replaces.

This is a musical, though, in which the production itself is the star. Much of its effect is the work of the gifted designer Maria Bjornson, who has created a magnificently ornate opera house, a shadowy underground labyrinth, a mist-shrouded lake dotted with candles and, everywhere, gorgeous costumes. Andrew Bridge's lighting is a dazzle of light and shadow.

In such settings, anything is possible - from a crashing chandelier to a Phantom hurling firebolts. Special effects such as these can, of course, be duplicated elsewhere. Here, they are among the elements that draw us into a haunting world, as irresistibly as the Phantom leads Christine into his subterranean lair.

__________________

Music Of The Night: THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA

Music by Andrew Lloyd Webber Lyrics by Charles Hart and Richard Stilgoe; Book by Stilgoe and Lloyd Webber

Reviewed by William A Henry III for TIME magazine, Feb. 8, 1988

Even if The Phantom of the Opera were the greatest show on earth, probably nothing in the way of actual experience could measure up to the hoopla that preceded last week's U.S. debut of the monster-meets-girl musical. No previous offering in Broadway history has rivaled the $18 million advance sale for Phantom, a commitment made by hundreds of thousands of people to pay up to $50 a ticket, generally before having had a chance to hear any of the songs, read any reviews or acquire the vaguest familiarity with the imported-from- London stars.

Some of the show's lures are known commodities: Composer Andrew Lloyd Webber (Cats, Jesus Christ Superstar) and Director Harold Prince (Cabaret, Follies) have mounted some of the flashiest spectaculars of recent years, including their prior collaboration, Evita. Practically everyone, it seems, has seen a movie version of Phantom, although few have read Gaston Leroux's turgid 1910 thriller about the hideously misshapen genius who constitutes himself the shadow ruler of the Paris Opera House and, upon becoming infatuated with a chorine, maneuvers her career from afar. The beauty-and-the- beast theme and subterranean wonderland setting echo the myths of Persephone, Pygmalion and Faust and also contemporarily embrace Freudian metaphors of sexual awakening. The Broadway launch has been boosted by publicity about Phantom in London, where, since its debut in October 1986, virtually the only way to get in on short notice has been to belong to the royal family: the Princess of Wales, a particular fan, has attended four times.

These rational factors go only part way in explaining the extraordinary anticipation that Phantom has aroused. The show apparently taps into yearnings for a transporting sensory and mystical experience: in a word, for magic. On that primal level, despite considerable and at times embarrassing shortcomings, Phantom powerfully delivers. The story may be muddled, the characters sketchy, some performances shallow and the music often slushily derivative. So what. For those who seek an equivalent to a ride through the Haunted Mansion at Walt Disney World -- seemingly a vast proportion of today's Broadway audience -- Phantom is a brilliantly manipulated journey, scary yet ultimately unthreatening. A prime example is the show's most celebrated effect, the gasp-evoking plummet from the ceiling almost to the floor of a 1,500-lb. chandelier. Many spectators arrive knowing it will drop, and the staging gives plenty of clues to the rest. Equally, however, audiences can trust that the "danger" will be averted at the last possible minute, so the dread is purely titillating, without a hint of life's real pains and perils.

The Phantom, described as a scholar, seems more a necromancer, dematerializing, teleporting, even dodging bullets. He defies the laws of gravity and physics: his kingdom in the bowels of the Paris Opera House is reached by rowing across a subterranean lake through which candelabra rise and descend, mysteriously unquenched. The lagoon seems to be at or above the level of his hideaway, yet his chambers remain unflooded. Allow oneself a moment's skepticism and the story turns to piffle. But audiences give themselves over to the fantasy concocted by Prince and Designer Maria Bjornson, letting logic evanesce as long as the sights and sounds are glorious. Which they are: bolts of lightning, carpets of fog and flashes of fire compete with the Phantom's midair descent in a chariot of gilded cherubs and his final disappearance while sitting on a solid-looking throne.

These effects are meant to be balanced by a love story, or rather two competing ones: the conventional passion between a handsome young vicomte and a chorus girl, and the dark, obsessive bond between that same young woman and the Phantom, who seeks to win her devotion by making her a star. The maiden is thus expected to choose between outward beauty and the beauty of the soul and, in protofeminist fashion, between status as a rich man's wife and acclaim as an artist in her own right. As befits a fantasy, she gets both by virtue of a brief display of compassion.

The three principal roles are again played by the actors who originated them in London, and therein lies the show's chief weakness. As the Phantom -- musically, a tenor good guy rather than a baritone baddie -- Michael Crawford gives the most compelling performance currently to be found on any Broadway stage. The character is an extortionist, kidnaper, incendiary and murderer. Yet as Lloyd Webber conceived him and Crawford plays him, he is also a romantic capable of true selflessness and is all too easily forgiven. As his rival, Steve Barton is blandly tuneful and smugly self-assured, which is all the role demands. The narrative tension is meant to emanate mainly from the virginal Christine, the part Lloyd Webber wrote for his wife Sarah Brightman. Vocally she has the needed equipment: her soprano is clear and sounds youthfully innocent along a wide range. But as an actress she has learned almost nothing from years in the role. Her vocabulary of gesture is limited to a flutter of hands and a gape of astonishment, accented by huge black circles of makeup around her eyes that cause her to resemble a raccoon. Brightman's Maypole figure, long nose and prominent overbite do not aid in explaining why both men adore her. But these deficiencies might be overcome if she displayed the least hint of star quality, or even stage presence, instead of acting like Minnie Mouse on Quaaludes.

Lloyd Webber gives his wife every help, beginning with her vocal introduction. Although Phantom is garlanded with opera pastiche, it subliminally nudges opera aside in favor of pop by offering the winsome ballad Think of Me first in the overripe, rococo style of a diva (Judy Kaye), then in Brightman's appealingly unadorned rendition. The device hints that the Phantom and his chosen instrument will become the means for remaking musical entertainment. If that claim is to be taken as Lloyd Webber's judgment of his own role in the theater, however, it seems premature. His knack for crafting hit tunes is offset by their interchangeability among characters and situations, plus a tin ear for lyrics and lyricists. Moreover, nothing in Phantom compares with Memory in Cats. The melody that comes closest, The Music of the Night, contains a repeated phrase that seems to quote Come to Me, Bend to Me from Brigadoon, a show that had true magic, fantasy and romance and that embodied a tradition of Broadway quality Lloyd Webber has not come close to matching.

__________________________

A grand 'Opera'

By HOWARD KISSEL

NEW YORK DAILY NEWS, January 27, 1998

PHANTOM OF THE OPERA. By Andrew Lloyd Webber, Charles Hart and Richard Stilgoe. With Michael Crawford, Sarah Brightman, Steve Barton and others. Sets and costumes by Maria Bjornson. Directed by Harold Prince. At the Majestic.

Contrary to what you might imagine, "Phantom of the Opera" is more than just a show about a chandelier.

Andrew Lloyd Webber's musical version of the fable about the masked man who haunts the Paris Opera is a longing look back at the stagecraft, the sense of wonder, theater had a century ago.

It is a spectacular entertainment, visually the most impressive of the British musicals. Perhaps the most old-fashioned thing about it is it's a love story, something Broadway has not seen for quite a while.

To say the score is Lloyd Webber's best is not saying a great deal. His music always has a synthetic, borrowed quality to it. As you listen you find yourself wondering where you've heard it before. In this case you've heard a lot of it in Puccini, in the work of other Broadway composers and even the Beatles.

Nevertheless he seems to be borrowing from better sources, and he has much greater sophistication about putting it all together. There are some droll opera parodies, several beautiful songs, an impressive septet and a grand choral number, all richly orchestrated.

His lack of originality is apparent in the music he writes for the Phantom's opera, which is merely harsh, not interesting. There is also a sequence with a heavy rock bass so cheap it might have been composed for "Starlight Express." Nevertheless, the score has an undeniable romantic surge. And after all, when was the last time you heard an unabashed love duet on Broadway? That accounts for much of the "Phantom's" appeal.

Much of its success is due to Michael Crawford's powerful performance as the Phantom. Crawford is strong both at underplaying the Phantom's villainy and at getting the maximum out of his final anguish. Steve Barton, as his rival, is an equally forceful singer and stage presence.

In the role of Christine, Sarah Brightman is fine. She has a cultivated soprano voice, a bit coy-sounding at times. Clearly her husband has written the music to demonstrate her range. The sound, however, is not warm, and her work seems very calculated. As an actress, she's not special. (Oddly, her eyes are so heavily made up they recall Lon Chaney in the title role.) Was she indispensable? Hardly.

Judy Kaye is funny and vocally impressive as a rival singer, and Leila Martin is strong as the Phantom's ally. David Romano is delightful as a comic tenor. There are no weak links in the cast.

What sets "Phantom" apart is the extraordinary imaginative work of Maria Bjornson, whose sets and costumes are a breathtaking, witty, sensual tribute to 19th century theater. Her constantly unfolding magic is hauntingly lit by Andrew Bridge.

The characters are not fleshed out, the lyrics are forgettable and the melodramatic plot is not as evocative as it might be. (Crawford's grief in the last scene is almost too deep for the material.) Nevertheless, that master conjurer Hal Prince has woven these seemingly outmoded materials into a grand evening of theater.

As for the chandelier, I should probably bemoan the attention focused on a "special effect." But I can't be upset to hear people gasp as it sways above them or give faint cries of delight as it swoops over them.

No one is really scared, especially since they've been reading about it for the last year and a half. As someone who knows theater must please more than just the mind, the sheer fun of the chandelier and "Phantom" seems a happy sign for Broadway.

________________

The Phantom Of The Opera

(Majestic Theater, N.Y. $50 top.)

By RICHARD HUMMLER for VARIETY

The London audiences aren't wrong. "The Phantom Of The Opera" is romantic musical theater hokum in the grand manner - hokum cordon blue - and it justifies the feverish buildup that has given it a $16,500,000 advance. It's good for a Broadway run of several years.

Andrew Lloyd Webber has taken the Gaston Leroux potboiler about the love-crazed disfigured genius who lives in the catacombs of the Paris Opera and fashioned it into a thrilling and musically rich mass legit entertainment. The 19th century period spectacle, scenic legerdemain, soaring melodies and exceptional singing are at the service of an involving and piquantly offbeat love story, all of it staged with brilliantly organized flair by Harold Prince, back in top form.

Given the near-hysterical anticipation aroused by this latest, big bertha West End musical smash, "it's not that good" will probably become a familiar refrain along the byways of Broadway. No, it's not "South Pacific" or "Fiddler On The Roof," but it's a major achievement in the musical theater and a high water mark in the phenomenal Lloyd Webber career. The bonus this time is that the glittering technical wizardry and pop-opera music have been wedded to a strong story and characters.

Chill-seekers may be disappointed, because this is a romantic "Phantom" in which the title hero is a sensitive artist ravaged by unrequited love, and not a rampaging early slasher. Lloyd Webber and co-librettist Richard Stilgoe have put the emphasis on the beauty-and-the-beast theme and develop an affecting yarn in the scarred recluse's obsessive passion for the beautiful opera chorine.

The show has a flashback structure, opening in 1911 with an eerily effective auction of props from the Paris Opera and jumping back to the 1881 melodramatics when the supernaturally gifted dungeon-dweller terrorized the theater. The period glitz is an eye-popping delight, with the onstage and backstage atmosphere artfully heightened but not cartooned.

The authors lay in the exposition smoothly, then move into high gear as the masked man of mystery whisks the entranced actress to his dungeon lair at the nether side of an underground lake beneath the opera house. The trip's a visceral pip as he ferries her to his cave across the lake lit by scores of candles rising from the water, to the throbbing music of the title song.

Few if any "Phantom" -goers will remain unhooked as title roler Michael Crawford seduces the dazed heroine in his candelabra-lit hideout to the propulsive chords of "The Music Of The Night," a patented Lloyd Webber rouser and a model of dramatic musical construction.

That's just one among an abundance of big-melody tunes in a great score that evokes period Hollywood film music, opera grand and light, operetta and especially pop Broadway of the classic era. The love ballad for heroine Christine and her aristocratic swain, "All I Ask Of You," is irresistible and worthy of comparison to Rodgers and Kern.

Not the least of the show's pleasures is the pride of place it gives to vocalizing. No musical in years has had better singing. Sarah Brightman's voice gets a through workout, and while it may not be of premier operatic quality, it's a lovely lyric soprano ideally suited to Lloyd Webber's clever music.

Crawford shows himself to be an exceptional singing actor who knows how to vary his sound for dramatic effect. And Judy Kaye, playing the large-ego diva whom Brightman supplants, sings the opera parodies with pleasing skill. The choral singing is clear and full-bodied.

The show's stagecraft is sensational, with scenic transitions that dazzle with their speed and ingenuity. Maria Bjornson's designs are marvels of period atmospheric detail and technical savvy (that Tony can be bestowed right now), and the costumes are grandly extravagant fun.

From Prince, it's the best show business staging since "Follies," always theatrical but in tight focus for the key moments of dramatic import.

Playing behind a mask, Crawford makes a fully developed human figure of the larger-than-life mad genius. His climactic scene with Brightman, as he sobs at her expression of love, has real pathos and moves the audience.

Brightman, as noted, is an exceptional singer and a competent if less than overpowering acting personality. Judy Kaye makes and expert pro's contribution as singer and comic actress. Steve Barton sings robustly and acts forcefully as the straight-arrow winner of the heroine's heart. Leila Martin, Cris Groenendaal and Nicholas Wyman supply accomplished performances in the secondary roles.

If it can't be said that "Phantom" advances the artistic frontier of the musical theater, it's more than welcome as a gloriously old fashioned romantic musical spectacle. And while Lloyd Webber may not be the most original of composers, he's an undeniably great showman with a seemingly unerring sense of popular taste. He's making musical theater history, and "Phantom" will be making musical theater money for years to come.

____________

____________

Any others that can be added to this collection greatly appreciated!

By FRANK RICH for the NEW YORK TIMES

Jan. 27, 1988